09 | 11 | 2001

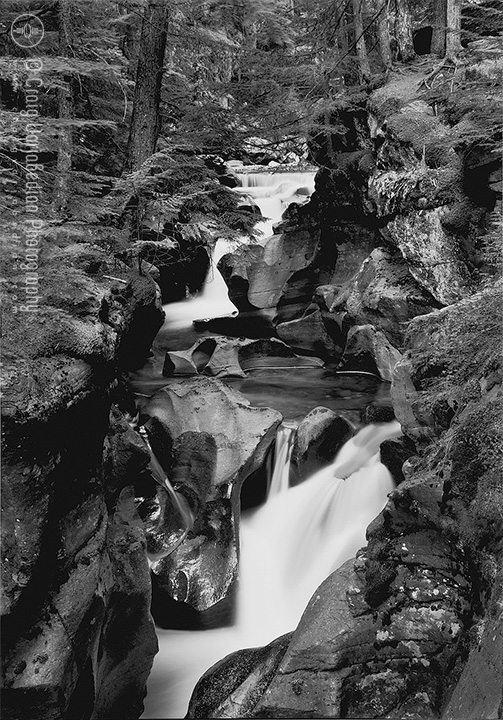

This is, I think, a beautiful photograph, but the day I took it was of one of the most horrible and tragic in United States history—September 11, 2001, the day of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I will never make sense of that event. Every time I look at this photograph I think about that day and how no one old enough to remember it will ever forget where they were on that awful morning.

My friend Paul Cousins and I were in Glacier National Park in Montana. Paul had been telling me about this magical place along Avalanche Creek for several years, and I knew I wanted to make a photograph of the waterfall in the soft light of early morning. We set out at first light from our little motel, but there was no real sun—the sky was overcast and everything seemed softened. We got to the park about 6:00 a.m. and headed up the trail. I was hiking with a fifty-pound pack and feeling every pound of it. Paul kept saying, “It’s just ten more minutes,” but as is always the case on hikes, it turned out to be another half hour. But when we got there, it was a beautiful view and I did want to make a picture of it. So I looked around and thought and measured. I planted my tripod about fifteen to twenty feet off the trail (I had permission) and got to work.

I hadn’t had my coffee and I was muttering under my breath when we heard footsteps. We looked up to see a park ranger on the trail. He spoke to us: “Have you heard about the airplanes that crashed into the World Trade Center?”

Six in the morning in Montana is 8:00 in New York, so it must have been about 7:30 or 8:00 Mountain time when we heard. The plane had just crashed into the Pentagon as well. I don’t know how the ranger knew about it or why he was on the trail; maybe he needed to get away from the horror of it.

I remember thinking, “This is terrorism,” and worrying about my family, even though none of them was in New York or Washington. But I knew that friends and acquaintances might be suffering.

Paul said, “Go ahead and photograph the waterfall.” He didn’t dismiss the events or our feelings about them; he just reminded me to do my work. At the moment that was to record the beauty around us, even as our brains were beginning to conceive of the pain and chaos that must be gripping the nation.

So I made this photograph. I made a deliberate decision to leave the shutter open for about eight seconds, so the water appears as if it is a veil flowing down the rocks. If I had kept the shutter open for a shorter time, the water would have appeared frozen, giving it a glassy effect. I wanted it to have a sense of movement. At one time I had done a series of tests of moving water to determine how I wanted to render it in my photographs. So I knew how long I wanted to expose this scene.

Other photographers have made pictures of water that is rendered softly—William Henry Jackson comes to mind. He had no choice. The photographic emulsions of his day, the early 1870s, were extremely slow and required long exposures. Many older photographs render water this way. I like that. I like it that my work sometimes harks back to another time, even though I use today’s modern films.

Paul and I went back down the trail and drove to park headquarters at Apgar. The managers at the hotel there had taken televisions out of the rooms and set them up on picnic tables, and every channel was tuned to the East Coast. People were clustered around the tables, watching. As I stood there and looked at the line of television sets, I could see multiple images of the airplane crashing into the World Trade Center.

We heard that airports across the country had been shut down. Travelers were stranded and businesses closed. We couldn’t tell which newscast to believe; there seemed to be no real clarity. Paul and I headed for the phones. It took a while, but by afternoon we had spoken with all our family members and knew that our immediate circles were safe.

Paul and I had a truck—we weren’t dependent on the airlines—so we discussed what we should do. Go home? Stay and continue photographing in the park?

Thinking back, I feel now that our decision—to stay and photograph—was influenced by that pristine moment at the waterfall. Despite all that was going on, we were witness to a haven in the Montana wilderness. The water rushing down the rocks was a natural phenomenon, far removed from the horrible image of falling buildings. The waterfall was, to me, the stronger image, and I wanted to stay, in defiance of anyone who would try to keep me away from beauty. I could not, nor ever will, forsake my love and passion because others would deny or threaten me.

The excerpt above is from my book Four & Twenty Photographs: Stories From Behind the Lens published by the University of New Mexico Press. The book is available at my studio store, through most retail bookstores and Amazon.com Photographs and Text Copyright ©Craig Varjabedian. All Rights Reserved.